Colorado Shopper Baffled by Mysterious 2.5% PIF Charge Where’s Your Money Really Going

The spooky season doesn’t start for months, but one Colorado flight attendant just received a scare.

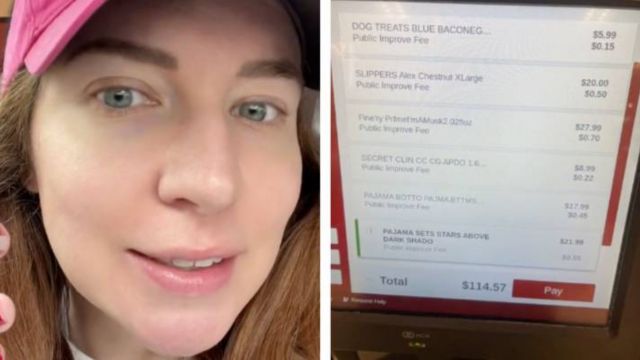

Holly Teska, a.k.a. @hollyintheclouds on TikTok, recently recorded a one-minute video chronicling her self-checkout nightmare at Target, which included an unexpected 2.5% “public improvement fee” on her bill. Keep in mind that this applies per item. The dog treats. Pajama bottoms. Every single item.

She posts a photo of her itemized receipt for $114.57. The math may seem simple since a 2.5% PIF should equal $2.86. However, the PIF is then subject to Colorado’s 2.9% sales tax, which can be perplexing unless you’re standing in line next to an accountant.

To coin a phrase, Teska sounds PIF’d off.

“Things are getting out of control right now,” she tells me. “I am asking, ‘Isn’t that what sales tax is? … “Target, Target, Target! I need answers!” In case Target CEO Brian Cornell didn’t hear it, she murmurs it once again in the video’s closing second: “I need answers!”

Teska would normally seek to stake out Denver’s State Capitol. But she’d be looking in the wrong spot. It turns out that the PIF is a tax that isn’t truly a tax—here’s more.

The PIF conspiracy thickens

Steve Staeger, also known as Steve On Your Side, a consumer advocate reporter for Denver’s NBC station, KUSA-TV Ch. 9, became aware of Teska’s TikTok. The 16-time Emmy winner embarked on an “undercover” investigation in the Denver region, purchasing 20-oz. bottles of Coke (which he substituted for San Pellegrino mineral water at a nearby Whole Foods).

It’s safe to believe he intended the word as a jest. However, given the tiny 12-point typeface for “Public Improvement Fee” on the crinkly receipt, hidden may be an understatement. Staeger described PIFs as a “mystery.” At other stores, the PIF dropped to 1.5%. Aren’t local fees expected to be consistent?

His 9News article also ran on YouTube, where it received 1 million views in eight days. In it, he speaks with Jeff Peshut, a real estate lawyer and assistant professor at Metropolitan State University of Denver, who describes how property owners and developers use PIFs to make physical changes to their tangible assets. Peshut notes that they may be used to pave the parking lot or to protect other types of vehicles, such as those used for financing.

And yes, that is all legal. PIFs have been in place in Colorado for more than two decades, with some saying that they fund infrastructure improvements that prevent malls and other similar structures from deteriorating.

But, despite their name, PIFs are not at all public; the monies flow directly to developers. “It’s another financing vehicle,” said Peshut, who suggests a better term for the acronym: “privately imposed fee.” In the alphabet soup of land agreements, he said that developers are particularly interested in using PIFs as OPM (other people’s money).

Do PIFs exist elsewhere?

PIFs, as described in this article, are unique to Colorado and cannot be found anywhere else in the United States. There are some rough counterparts to public laws that safeguard private financial interests, but they are more rooted in political intrigue.

In Chicago, former mayor Richard M. Daley rammed a contentious 2008 deal through the city council that sold 36,000 parking meters to Morgan Stanley for more than $1 billion; today, public employees who write tickets are essentially paid to protect the pockets of the private owners, now known as Chicago Parking Meters LLC. (Three years later, Daley joined the law firm that brokered the contract.)

Back in Colorado, the people who built and run the Lakewood Target, which sparked the PIF controversy, might want to read the 3,000-plus comments on Teska’s video. Some urged a store boycott, while others criticized the absurdity of adding a PIF to inflationary pricing increases.

However, these business leaders may not care. But at least Teska has answers now.